Gypsies

I have lived in Madrid, the capital of Spain, for nineteen years. The common perspectives about otherness and race differ substantially from the United States’, partly due to a whole different reality of minorities and their historical backgrounds. Nevertheless, whiteness implies an extra value and is mostly related to patriotism, although I have never experienced it as strong, complex and constructed by Media as I have in my studies at Berkeley about America.

My personal experiences regarding problematic and racialized interactions revolve around two generic ethnical groups: Gypsies and Latin American migrants. Every lesson I got throughout my life has helped me to understand a social problem that always felt alien to me, since my family is not racially discriminatory at all. It also has helped me to contextualize race within a system of values and interactions in which, by institutional, violent, and media oppression, stabilized structures of power are maintained by any means. The creation of the other in Spain has been, however, much more based on economic criteria than on racial ones. In this essay, I am going to focus on my experiences and understanding of gypsies, a cultural and ethnical group mostly discriminated, whose members are often exposed to poverty.

Since racialization of space is one of the main factual reasons of racial discrimination, I consider important to review recent urban history in Spain and Madrid. My family moved to the suburbs in 1997. Spain was getting out of a crisis rooted in the incompetence of the socialist party (PSOE), which had been governing the country since 1982. In that period of time, Spain suddenly became a developed country. Actually, the national economy kept the progressive path that started with the Developing Plans in the sixties, under Francisco Franco’s dictatorship (1936/39-1975), which practically meant adapting resources to capitalism. The PSOE applied certain socialist measures, rather focused, however, on a social level (universal health care, divorce, abortion, free education). As it happens when cities offer jobs, the Developing Plans drew the workforce from the countryside to the cities, where most of them settled in the suburbs under poverty-stricken life conditions. Urban plans from the fifties allowed the construction of infinite cheap and extremely unpleasant housing projects (around 400,000) that today, for their geographical location, are still overrated. Also, the increasing urbanization and a certain stabilization of labor led to private, (also monotonous) peripheral projects from the sixties, a pattern that would lead to small and apparently beautiful private estates in the 80s and 90s for middle-class workers who wanted to fulfill their dreams (educated they were in a dictatorship in which poverty and corruption ruled). My parents are included in the last group. In between, another important trend in urbanization was the shanty towns that started developing in the suburbs of big cities in the 40s, normally inhabited by Portuguese and Spanish gypsies.

Problematic spaces arose from the confrontation in the suburbs between shanty towns population and residential estates. The construction of residential estates brought to the suburbs the city. My neighborhood, Mirasierra, got an Underground station last year, and some yards from it the city is already over, and El Pardo, a natural reserve, stands as the only barrier that stops civilization. However, Mirasierra is not an average suburb area. It began in the fifties as a colony for American soldiers that worked in a military area, becoming one of the wealthiest neighborhoods in the north of Madrid. The capital, however, was growing by itself from the south, and soon the public projects starting in the 60s (Peñagrande and Barrio del Pilar, the latter already an old settlement) collided with the big and unpolluted houses of Mirasierra, separated by a highway, Avenida Cardenal Herrera Oria (named for a Catholic fascist), known before by “The Beach avenue”, since it leaded to a river where many Madrileños used to spend the sunny weekends. At the same time, in the late 80s and 90s a whole different project of housings (the nice estates I mentioned above), partly subsidized by public funding (the source of which was soon denounced for fraud and corruption, related to the PSOE’s national union, UGT), were built around Lacoma, a colony for working-class people from the 50s: Mirasierra in the West, Barrio del Pilar and Peñagrande in the South, and another neighborhood with similar historical background (including a wealthy colony, Colonia de Hierro, where ex-Argentinian dictator Juan Domingo Perón used to live), in the East. In the North the landscape, the mountains in the background, El Pardo in between.

Nevertheless, there are indeed houses in that frontier, on the way to El Pardo, crossing the train tracks. Most of them were there as parts of isolated communities whose inhabitants used to work in the area. Others were -and still are- chabolas, houses made by construction residues, cardboards, metal sheets, panels, lacking a water system, a electric network, an asphalted road. That is to say: shanty towns. A report by El País in 2005 about chabolas offers valuable information: around 5,000 Madrid inhabitants lived in 1,400 chabolas. The report actually mentions Pitis, the last part of my neighborhood.

“The 90% of the chabolas are settled in the capital. The shanty town Pitis, close to the train rail that crosses El Pardo, is one of the oldest settlements still existing. It is 19 years old. Official info establishes that it is ‘dismantled’, since the majority of the 99 chabolas were destroyed thanks to the Plan of Elimination of Substandard Living. Nevertheless, the county recognizes there are still ten chabolas, waiting for a court order to also vacate them” (translated by me)

That is the history of Pitis. Pitis, today only a train station from which I can go faster to Getafe, the city where my home university is. Pitis used to mean a whole imagined world to all my mates in primary school. First of all, because it was the place where they lived, second, because it was actually a place you could see, walking five minutes from my house, going close down a hill where still there is a beautiful park where people hike with their dogs and the youth play soccer and basketball. Next to the chabolas the Cemtro clinic is still functioning (where all the soccer stars go to recover, where Jesús Gil, ex-mayor of Marbella, corrupted, millionaire, owner of a soccer team, died in 2004).

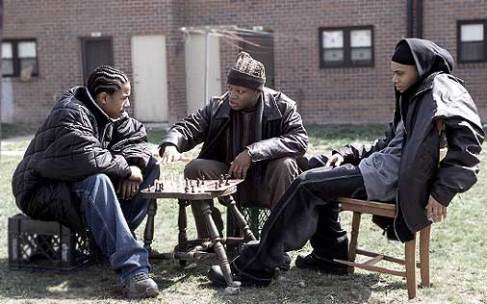

Pitis was like the Celtic colony of Asterix and Obelix. Surrounded by Romans, by civilization. Some of the children of the town went to the same school I went, Colegio Público Mirasierra, the only public school in the neighborhood (El Prado and El Montealto belongs to Opus Dei, Los Jesuítas and Sagrado Corazón to other religious orders). They were gypsies. They were outlaws. They were not Portuguese. They were terrifying, or so they became. I remember being 4 years old and playing with Fatima, a girl with black teeth who smelled funny. I did not even know what gypsy was. But other friends of mine did not like her, and me, of course, with a completely childish and innocent mentality, did not understand what was going on until a long time passed. I remember walking around the patio in the break after lunch, bumping into one of them, one of the kindest, telling a story about how he stole a car with his brother to ten seven years-old kids; talking about a whole world that most of us did not know at all. They were ten, maybe less, maybe more. Everybody knew them. They got into fights, did not come to class, talked back to the teacher, and ruled the breaks. Around that time I had my first (and only one) problem with them. With Cheche, practically a legend. He was old, still in primary school. There were crazy stories about him. My opinion about gypsies was still neutral, my parents never allowed me to discriminate them through comments. They were our problem. We made them. Their poverty was our fault. We had to help them. But still they were terrifying for me. Cheche pointed me with a laser in a break and I told the teacher, who took the laser away from him. Since then, Cheche asked me for the laser every single day for a year, some days violently, luckily it never actually got violent. My parents did not listen to me at all and I did not know what to do. I never went out of my neighborhood by myself, I did not know at all where I could (and with what money) buy a laser. It was a nightmare and my parents finally got involved. They talked to the headmaster, who refused to give the laser back at first. It kept going on and on, as in Demian, by Herman Hesse, until the situation got normalized and was not violent anymore. One day he shouted at me and, smiling, waved the laser with his hand, showing he had finally got it.

At that point, my vision of gypsies was even more contaminated by small anecdotes. I remember a girl that spent a whole break catching my jacket, not letting me move. There was nothing (I thought) I could do but wait, since touching one of them was touching the whole family, and that was the last thing I wanted. It could have kept like this, but I got closer to Laura Albaladejo. She lived in my neighborhod. Now a really good friend of mine, and a social worker, Laura has always had incredible social skills. She knew all the gypsies. We were nine years old and Laura used to talk to them, stop them when they wanted to fight, laugh with them. One day, I saw Cristobal and Andrés (cousins of Cheche, who was no longer in the school) on my patio. They were clean, well dressed. Laura and her mother had invited them to have dinner at their place. They smiled at me, they said hello to me. I remember that as a turning point. I started listening to Laura’s stories. Except for the fact that they all had already asked her to marry them, they treated her as a friend. They listened to her, they told her their stories; and they also got violent, shouted, ran away, didn’t go to class. They were different, they had been raised in a completely different culture, with a lack of resources I did not believe as part of my reality. But it was there. Right down the hill. I remember staring at it from the hill, next to the benches, a metal roof, the dogs, the old people. Looking at it and thinking about going down. It was about braveness. We never did it.

In 2004, they took the chabolas out. From one day to another the chabolas were gone. I didn’t see any of them again. Some roads were constructed, the land was flatted, street lights and benches, as any other average suburban street, decorated it all. There is nothing there. Only fences and roads you can hardly cross in order to take the train at Pitis’ station.

The other way I learnt about gypsies was art. First, Federico García Lorca, one of the best poets of the 20th century who was murdered in the beginning of the Civil War, homosexual, andaluz, from a wealthy family in Malaga. The 90% of Spain’s chabolas located in Andalucia (one of the most populated, poorest and interesting counties in Spain) are inhabited by gypsies (300,000), who are implicitly linked to flamenco, the most idyosincratic music of Spain. Therefore Andalucia is their home more than any other place (and the 22nd of November is their day). However, due to the formal prohibition of discriminating by race, it is difficult to find actual information about the number of gypsies. The ethnic history in Spain is not clear nor enough studied yet, but references by authorities, writers, and painters portray them as nomads, full of life, related to delinquency and smuggling. They were commonly seen as different, unable to adapt, with their own culture that in some cases was against Spanish values. Federico García Lorca wrote between 1924 and 1927 “Romancero Gitano,” “Gypsy Romance”, which contains stunning poems in which gypsies are sometimes followed, oppressed, or murdered by the guardias civiles, a certain type of police. The civil guards and the gypsies had been traditionally enemies, and that vision is embodied in Lorca’s work, from which we understand the abuse of power the civil guards constantly exercised. The next poem, for instance, although pretty abstract (Lorca is related to avant-garde movements after the First World War in Spain, The Generation of ’27), could tell the story of a kid that is followed by the civil guards, who end up murdering him, all under the gaze of the moon, symbol constantly used by the author and pretty related to the gypsy culture. Here is the poem in English, and here in Spanish, along with all the other poems of that publication.

With a child by the hand

through the sky goes the moon.

Inside the forge

the gypsies cry and scream.

The air keeps on in vigil.

The air its vigil keeps

Second, flamenco. Most of the best flamenco musicians (and also dancers) are gypsies, and that means that they have grown in an atmosphere in which music occupies an vital place, an element also part of blackness in America. Of course, not all the gypsies live in chabolas. Today, only the 5% of them do. Their life expectancy is 8-9 years less than the “payos”, what they call white people (rather cute than discriminatory). From Niña de la Puebla, traditional flamenco, to Camarón, Lole y Manuel (whose song “Tu Mira” is on the soundtrack of Tarantino’s Kill Bill), and Paco de Lucía, going through Triana, and coming up with Enrique Morente and his daughter, Estrella Morente, whose famous cover of Carlos Gardel’s “Volver” gives title to the best Pedro Almodóvar’s film; flamenco, which my sister dances and my parents have listened to since they were my age, is also a part of my life. Last, one should mention the attempts of some organizations and people to construct a feeling of community around the gypsies in the world, especially in the European Union, where gypsies are the biggest minority. Romani, gypsies, gitanos; I also got to know more of them through a whole different scenario of Romani in the world: the Balkans, in which the music, as the Spanish flamenco, is absolutely linked to the gypsy communities.

The lesson I got from my living experiences reinforce an idea that has existed in Spain, related to the exclusion of gypsies, for many years: measures of inclusion hardly work. Making the gypsy children who live in chabolas go to school without any other plan is absolutely ridiculous. They lose any kind of self-esteem and grow envy and jealousy towards their class mates, apart from not being able to help their families economically anymore; the others, us, grow a huge fear that is constantly treated as euphemistic, as if they were a minor threat we have to deal with. As if they were not humans. The cities have been dealing with “the gypsy problem” for a long time, constructing 100% free projects, finding jobs for them, incorporating them to normality; which could imply the loss of their culture, absolutely peculiar, special, legendary. El País published an editorial comparing the inclusion models of Spain and France, and recognizing the value of Spain’s measures, which are a “referent” in Europe. What about Rumian gypsies? Perhaps the gypsies are never going to stop being nomads. Or maybe the strength the system has incorporating and neutralizing any subversive element is too weak for people that are everything but weak.

The other group, Latin American migrants, is still a working project. The children of the migrants that came in the late nineties and last decade were not from my generation, therefore I hardly have had interactions with them, except when I worked once teaching English in (curiously) UGT, that national union, which offers free courses to workers. They represent a whole culture I could not be more excited to know about. That is my project when I come back to Spain this summer.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

-Rafael Puyol Antolín. La población española. Madrid: Editorial Síntesis, 1990.

-Tomas Calvo Buezas. Voces payas sobre los gitanos. Barcelona: Anthropos, 1990.

George Lipsitz. How Racism Takes Place. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2011

-María Concepción Muñoz-Delgado. Geografía Bachillerato. Madrid: Editorial Anaya, 2003.