The Wire as experience and representation

by Chasen

In a day when crime rates appear lower than ever before in the United States, Gallup recorded in 2010 that most of the population felt crime had increased compared to the years before. The “fear of crime” is recognized as a social and political problem in contemporary societies, where Media spreads like an enormous net, establishing analogies with our physical reality that can be easily confused. The data mentioned above suggests a question: if crime has lessened, what are the people’ sources of information which generate the opposite feeling? The increasing entertainment content in which crime is a fiction element? The whole informational world the Internet allows? The newspapers, TV news, and other traditionally responsible agencies of covering social problems?

Scholar James W. Carey wrote in 1989:

Our minds and lives are shaped by our total experience- or, better, by representations of ex¡perience and, as William has argued, a name for this experience is communication. If one tries to examine society as a form of communication, one sees it as a process whereby reality is created, shared, modified, and preserved. (Communication As Culture, 1989; 33)

This paragraph could work as a peculiar bridge between Walter Lippmann and Jean Baudrillard. Lippmann, as a modern thinker, stressed the trascendental importance of journalism in interpreting and informing social and political realities, an arena too huge and complex for human beings. Baudrillard, as a postmodern philosopher, saw in last century’s world a cultural transformation which implied the creation of a never-ending simulacra of the reality humans were supposed to still believe as “real,” simulacra that progressively would substitute human experiences in a mere constructed frame, lost its original meaning, thereby lost the possibility of approaching a truth per se completely disappeared. Carey studied communication through the study of communication itself, introducing Cultural Studies’ elements into the philosophy of the Media, yet such a confusing and contradictory academic field. Underlying the role of the representations of experience as the shaping vehicles of lives and minds, Carey understood representation as communication, therefore neutralized the various perspectives the scholar was working with.

What is the current representation -or communication- which shapes people’s minds in a certain way about crime and fear? Crime became a movie star in the thirties, when the gangster genre provided a new, controversial perpective of the American idiosyncrasy. Television, however, brought into every American home the daily fight between police and criminals, within a ridiculously simple dichotomy society saw as the core of the morality for a long time. It seems appropriate to believe that the industrialization (aperture, explosion, re-conversation) of culture and art throughout the 20th century has shaped every single Western human being’s mind. May it, then, be the reason of American’s fear to crime? Should we keep resuming postmodern theories which relate people’s boredom and passivity to the enormous Media power some corporations and politicians convey in order to maintain, anyhow, anytime, anywhere, a status quo constantly perfected?

Scarface (Howard Hawks, 1932)

HBO, the channel that produced and screened The Wire, is property of Time Warner, the biggest Media company in the world. Time Warner also owns CNN, a global news TV often related to America’s values and perspectives outside the country. The ideological apparatus that Louis Althusser described as the esquema of Western societies imply the constant normalization of every activity, a “hegemonic negotiation” (Benshoff and Griffin) which allows this ideology to survive, “winning over the hearts and minds of a society”, reinforced more and more since it “functions most smoothly when it is so embedded in everyday life” that oppression is unnecessary, the scholars wrote for the introduction of America on Film. These theoretical reminders are, in my opinion, necessary base of any critical or analytical incursion in culture. The Wire, a singular product that exemplifies the rise of series production within TV in the United States, may not be only seen as an interesting, but still not critical enough product (as George Lipsitz stressed in How Racism Takes Place, which is commented below), but as a challenging and overwhelming experience. Film and video were born when the people, those masses, got free time enough to enjoy traditionally seen as ‘high art’ forms, category that finally adapted the cinema last century, but still looks reluctant to TV.

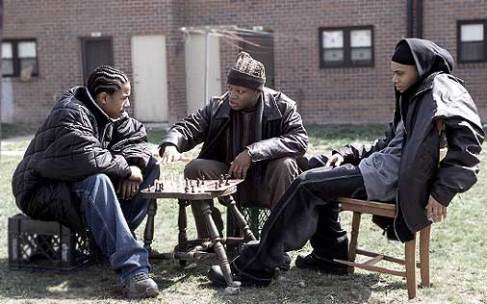

The projects from The Wire

D. N. Rodowick, director of the graduate program in Film and Visual Studies at Harvard University, affirmed in his essay “An Elegy for Theory“:

Where contemporary philosophy has reneged on its promise of moral perfectionism, film has responded, though in the preconceptual manner of all at and sensuous expression. Thus the great project of film philosophy today is not only to help reinvigorate this moral reflection, but to heal by example the rift in philosophy’s relation to everyday life.

Film, the audiovisual, seen as the ultimate culmination of art; art, as human expressiveness, beauty and intellectuality, seen as the vehicle from which we can convey philosophical meanings about a constantly changing reality. Why study humans when we can study humans’ products? The Wire is thus not only what it is depicted, but the fact that depicts parts of reality which have been constantly rejected in most of the Americans’ imaginary. This (our class) is in fact an incursion in culture, and any topic related to The Wire is for me unavoidable linked to philosophy. George Lipsitz, who got deeply inside the actual reasons of racial discrimination in the United States, stressed answers to The Wire I had never seen before. He saw the show’s pessimism as a “symptom of power relations”, as well as a embodied “neoliberal and conservative verdict of the civil right movements”. In one hand, the scholar is facing a TV show as an intellectual discourse which is supposed to contextualize the problematic issues it portrays in certain, analytical ways. Lipsitz, who establishes the racialization of space and the spacialization of race as the main forces behind American’s current racism, does not find in The Wire reflections to an idea he partly shaped two years ago. On the other hand, should The Wire be taken as an intentional and critical speech about the system? Let’s say it is: the critique thus becomes an improvement. The reader who already knows The Wire is able to connect the show’s representation of a structure to other aspects Lipsitz analyses, all of them working in the shake of revealing a reality constantly manipulated by every single participant in the process of cultural communication. The intellectual (social, human) dialogue between the show and Lipsitz creates a state in which what it is analysed is the representation of the representation of the experience, at the end made experience itself (as art).

The last idea, at least for me, could challenge some postmodern paradigms. Nobel winner Mario Vargas Llosa wrote in 2009 about Wallace Souza. A Brazilian Media magnate, Souza came into view thanks to Canal Livre, a TV documentary which covered many criminal cases that happened in the state of Amazonas. Souza ended up as a popular member of the Amazonas assembly, which made difficult for the authorities to arrest him. As Vargas Llosa narrates, an investigation discovered how Souza had developed a huge net of collaborators who were responsible for causing the crimes Souza’s most successful program would cover a few hours after they had happened. Vargas Llosa, known for his liberal opinions, mentioned Foucault’s and Baudrillard’s theories as “funny, intellectual made-ups” that after Souza were astonishingly supported; a mere wink to the academia, but also a reflection of ideas developed more than twenty years ago that now are easily probed in many incidents. Nevertheless, rather than formats like “America’s Most Wanted” which explicitly confuses reality and fiction (whatever the social intention and repercussion are), the audiovisual keeps developing ideas that, as The Wire, actually may present and discuss philosophical reasons and alternatives.

For the record, Vargas Llosa also wrote last year in the same newspaper about The Wire, comparing the show’s stories to those by Dicken’s or Duma’s, recognizing classic Greek patterns in its fictional character’s fates; elevating the series to the category of high art which he more than anyone represents today.

Last, still a simulacra of reality -according to Baudrillard- would be the police drive-alongs that took place in Richmond. I was part of the last group, which met Officer Stonebreaker a Friday night. It was the first time I was going to be in a police car. It was the first time I was going to talk to a policeman after the protests that happened in 2011 (and still happen) in Spain. My opinion about the police was paradoxical. In one hand, Louis Althusser‘s schema seemed to appear everywhere, thus the police was doing exactly what it was supposed to do as the repressive force of the state: make sure the law (the expression of power) was obeyed, and therefore avoid any kind of transformation which challenged power. On the other hand, the obvious fact that the police force is composed of human-beings was even more scarier, since it meant that most of them were not apparently capable of understanding their own role and their own lives. This course gave me that perspective linked to crime and streets, which I had only known through the Media before. Problematic gipsies and latino gangs during my adolescence, and neighborhood drug dealing some years after were all I used to know first hand of “crime”, a word easier to relate to fiction than to reality. The ride-along, however, was the routine of a dream from a god’s perspective. I was watching through the mirror and confusing it with a screen. Only the people looking at me made me distinguish between reality and fiction. Because in fiction, at least most of the time, nobody looks at the camera.

SOURCES

- Jean Baudrillard. Simulacra and Simulations. Selected Writings, ed Mark Poster. Stanford University Press, 1998

- Harry M. Benshoff, Sean Griffin. America on film: representing race, class, gender, and sexuality at the movies. Blackwell, 2004

- Timothy Corrigan, Patricia White, and Meta Mazaj: Critical Visions in Film Theory. “An Elegy for Theory”, by D. N. Rodowick (2007). Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2010

- Walter Lippman. Public opinion. New York : Free Press Paperbacks, 1997

- George Lipsitz. How Racism Takes Place. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2011